Swamp-flanked coastal plain rivers not uncommonly look like the pictures below, from the lower Sabine River along the Louisiana/Texas border. The river not only meanders, but the meanders and associated lateral migration are clearly active. This is evident from the minimally or unvegetated sandy point bars on the bend interiors and the active cutbanks on the outside of the bends.

However, even in the Sabine River, bends in the lowermost reaches of the river appear to be stabilized, with a full vegetation cover and fine-grained sediment rather than sand. Cutbanks exist but are less common and spectacular than some of those upstream. This is typical of many—not all—of the swamp rivers of the Carolinas coastal plain. These are often thought to be laterally stable—that is, not migrating side-to-side—because they don’t look anything like those pictures above. This post continues the theme in this earlier post on the varied and unusual channel patterns of our Carolina swamp rivers. Here we explore some evidence that these rivers are perhaps not as laterally stable and fixed as it seems.

A meander bend on the lower Neuse River, N.C.

If you don’t have an unvegetated, mobile sandy point bar, what evidence is there that a meander bend could be growing on its inside? Three indicators I’ve seen in the field are: (1) Shoaling due to sediment accumulation at the edge of the bend interior below the vegetation line; (2) Recent vegetation colonization on the outer edge of the bend interior; and (3) a clear successional gradient (younger to older) from the river’s edge.

Shoaling on bends of the Northeast Cape Fear River, N.C.

Recent vegetation establishment on a bend in the Neuse River fluvial-estuary transition zone (top), and on the Trent River, N.C..

Vegetation gradient on a bend of the Little Pee Dee River, S.C. (GoogleEarth image). River is about 50 m wide at the arrow.

Active lateral migration should have some indication of erosion on one side of the channel (at bends, on the outer bend). These indicators include erosion scarps, slump scars, undermined trees, and exposed roots.

Eroding banks along the Neuse River (top), Grinnell Creek (middle), and White Oak River, N.C.

In addition to field indicators, there are sometimes indicators of lateral movement from maps and imagery. These take the form of paleochannels, and ridges indicating former natural levees on the channel bank.

Shaded relief map of the Neuse River valley bottom downstream of Maple Cypress Landing. The elevation profile is along the line shown, from the left (north) side of the valley to right (Figure 4 from Phillips, 2022).

The examples below are from my recent article on tributaries and meander bends on coastal plain rivers in the Carolinas.

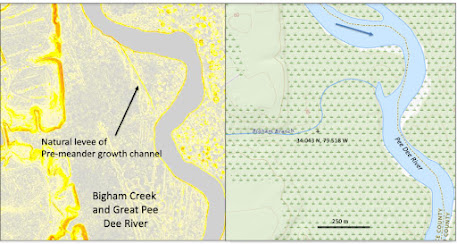

Confluence of Bigham Branch and the Great Pee Dee River. Left is a slope map

derived from 10 m-resolution DEM data. Gray areas are flat.

It is therefore a mistake to assume that our swamp rivers are fixed in place and laterally stable, though they move more slowly than some other alluvial rivers. In a future post we will explore why oxbows are so rare in the region.

References:

Phillips, J.D. 2022. Geomorphology of the fluvial-estuarine transition zone, Neuse River, North Carolina. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 47: 2044-2061. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5362

Phillips, J.D. 2025. River meanders, tributary junctions, and antecedent morphology. Hydrology 12, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12050101