When I went out this morning (in Myrtle Beach, SC), it looked as though a heavy fog had settled in. My eyes began to itch, and my nose quickly confirmed that the fog was actually smoke. Horry County, parts of it at least, is burning. Night before last, my son’s family had to evacuate their neighborhood (the upside was that we got some extra grandkid time, because we all crowded into our apartment for the night).

Fire in the Carolina Forest area of Myrtle Beach

(photo by Horry County Fire & Rescue).

As dangerous and inconvenient and costly as it is, this does not compare to many of the recent fires in the western U.S. But what makes it relevant to the Swamp Things blog is that much of what has been burned or is burning is forested wetlands. While wetlands do occasionally dry out and burn, you don’t really associate fire and wet areas. But that is increasingly going to change.

National Wetland Inventory (NWI) map for a portion of the Carolina Forest area recently and currently burning. The green areas are mapped wetlands; at the bottom of the figure, you can see roads from the ever-expanding subdivisions in the area. The NWI codes including “FO” are forested wetlands. The areas shown are mostly classified as seasonally flooded.

Climate attribution studies have identified the climate change drivers of increased fire frequency and severity in the west (and elsewhere). Though it is too soon to make that call for the South Carolina fires burning now, it is a good bet that more and bigger fires due to climate change are in the cards for the southeastern U.S. (if you doubt that climate change is happening, you are in the wrong blog, friend). Take a look at the figure below, produced using the U.S. Geological Survey National Climate Change Viewer . The tool uses outputs of 23 different climate models from 17 different sources or agencies. For this graphic the multi-model mean predictions were used. The viewer displays results for six different scenarios. In this case results for scenarios of 1.5, and 3o C warming were used. Changes are evaluated relative to a 1981-2010 baseline for three different periods: 2025-2049; 2050-2074; and 2075-2100. The figure below is for the Pee Dee River basin, but generally similar results show up if you analyze other areas of the region. Of course, temperatures will generally increase but so will (on average) precipitation. But what’s important for fire regimes is the balance between precipitation and evapotranspiration, which shows up in total runoff, soil moisture, and evaporation deficits (reflecting the difference between how much plant water use and evaporation would occur if moisture is always available, versus how much will actually occur).

Month-by-month predictions for the Pee Dee River watershed (South and North Carolina) under 1.5 and 3 degree C warming scenarios (the +1.5 is basically already upon us) reflecting the net balance between precipitation inputs and evapotranspiration outputs. The solid line represents the 1981-2010 mean; the predicted values (with error bars) indicate the deviations.

As you can see, it will almost certainly get drier, making droughts more likely. And more drought means more fire.

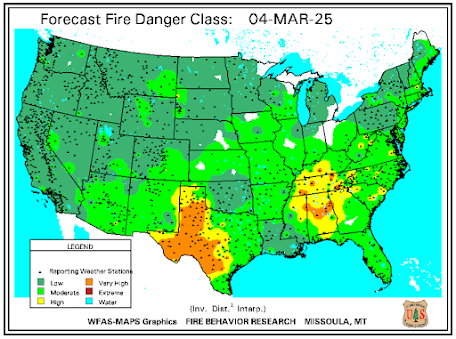

Some current outputs from the U.S. Wildland Fire Assessment System showing the dry conditions in northeastern South Carolina and the high fire risk.

Fire swamps

For many of us of the nerd persuasion, the term “fire swamp” conjures up scenes from the classic movie ThePrincess Bride, where the fire swamp produces not only frequent and unpredictable jets of flame, but is also the home of the notorious ROUS (Rodents Of Unusual Size). But, given that seasonally flooded and hydrologically isolated wetlands can and do burn (for instance, peat fires in the pocosin shrub bog wetlands of the Carolinas are not uncommon during dry periods), what about the deepwater swamps I am mainly concerned with in this blog? These are by their nature not prone to frequent fire and are by no means fire-adapted or even fire-dependent ecosystems like some others hereabouts (for instance, longleaf pine woodlands and savannas).

Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), swamp tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) and water tupelo (N. aquatica) are the iconic swamp trees. All have low to very low fire resistance. However, though fire is rare, it can be important in maintaining bald cypress dominance by reducing competition from broadleaf trees. Surprisingly, Atlantic and Gulf coastal plain floodplain and riparian communities have fire return intervals of 9 to 69 years, according to the LANDFIRE model of the U.S. Forest Service, 52 to 90 percent rated as low severity (1).

The upshot is that while our beloved swamps on hardly on the front lines of these particular impacts of climate change (as opposed to changes in storm frequency and severity and sea level rise), they are not immune—as the smoke in my eyes when I go outside reminds me.

Some video of the Carolina Forest Fire, from resident Greg Staff, via the Myrtle Beach Sun-News.

___________________________

(1) Fire Sciences Laboratory, 2012. Information from LANDFIRE on fire regimes of Gulf and Atlantic coastal riparian and floodplain communities. In: Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/fire_regimes/Gulf_Atlantic_coast_riparian/all.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment