Did you ever notice that along winding, meandering rivers, tributary streams almost never connect on the interior, point bar section of meander bends; always on outer bends or straight reaches? Basic principles of hydrology and fluvial geomorphology regarding flow dynamics in bends readily explain why it is difficult for tributaries to form on bend interiors, and why an inner-bend location is disadvantageous, and an outer-bend site is hydraulically advantageous for tributary junctions. But these generalizations largely apply to winding rivers with channel margin bars, often sandy or gravel, that are readily mobile, and banks that are not too difficult to erode.

Junction of Ashes Creek and the Northeast Cape Fear River, at the apex of a river meander bend. The leaves coming out of the creek show the flow dominance by the river.

But those conditions are rarely present on bends of the swamp-flanked rivers of the lower coastal plain. Both banks, including point bars on bend interiors, are typically fully and densely vegetated right up to the river’s edge. The bars are also often composed on cohesive fine-grained sediments rather than more readily moved sand. These rivers have been called “vegetation bound” by some scientists due to their perceived lateral immobility.

In addition, these lower river reaches are characterized by coastal backwater effects as astronomical tides, wind tides, and storm surges slow, block, and reverse downstream flow. In addition, banks are also very low, and sometimes nonexistent, with just a gradual transition from open water to trees standing in water to wet, frequently inundated floodplain.

Lower Waccamaw River, S.C.

In a nutshell, these lower coastal plain swamp rivers are quite a bit different than most alluvial rivers, and some of the generalizations about tributary junctions and meander bends may not apply. For example, on a sandy alluvial river meanders often start with a channel margin bar along what will become the bend interior. If there is a tributary junction, and if the main stream flow is significantly stronger (as it generally is), the bar will deflect tributary flow downstream. As the bend develops, the tributary is deflected toward the downstream end of the bend. If there is an incoming tributary on the outer bend, by contrast, the erosion on the cutbank shortens its channel, thereby steepening it, and promoting its staying on the outer bend. Sandy, unvegetated point bars are rare in the lowermost river reaches (fluvial-estuarine transition or tidal freshwater zones).

From my paddling these rivers, my impression was that the pattern (tributary junctions only on outer bends or straight reaches) generally holds in these systems, especially for larger tributaries, but you can see some small channels on the low, wet, bend interiors.

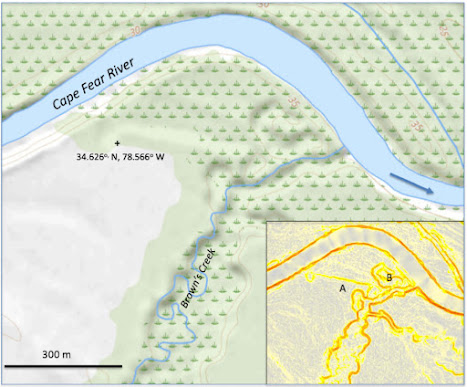

So, with some additional fieldwork and GIS analysis, I examined 121 tributary junctions along the lower reaches of seven South and North Carolina Rivers, as well as a number of other river bends that did not appear, on maps and imagery, to have tributaries.

Indeed, the no-confluences-on-inner-beds pattern holds true in these environments. None of the 121 tributary junctions occurred on bend interiors, with about half on outer bends and half on straight reaches of the main stream. The small channels occasionally found on inner bends all turned out to be local distributary/tributary channels where water flowed into the floodplain bend interior during high water and back again as river stages fall. None extended beyond the local floodplain.

Confluence of Bigham Branch and the lower Pee Dee River. Image on left is slope map derived from digital elevation model data.

Confluence of Bigham Branch and the lower Pee Dee River. Image on left is slope map derived from digital elevation model data. One key lesson is the importance of antecedent topography in these settings. On outer bends, the pre-bend topography is eroded away as the bend develops. On inner bends it can be preserved, and this is especially the case in the study area. The dense plant cover (and often fine, cohesive soils) slow down lateral migration of the river, but allow for preservation of paleochannel features.

Another is the local nature of gradient selection. In many cases extension of the tributary across the growing bend interior would have allowed for a shorter, overall steeper path to the river. However, flowing water can’t “see” anything but its immediate surroundings, and the remnant river channels provided a steeper, deeper, easier path at the point where they were encountered.

This work was recently published as the article referenced below, from which the figures above came (it is open access, so you can get it for no cost). The abstract is also below.

Phillips, J.D. 2025. River meanders, tributary junctions, and antecedent morphology. Hydrology 12, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12050101

No comments:

Post a Comment